[Editor’s Note: John C. Ellis, Jr. is a National Coordinating Discovery Attorney for the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, Defender Services Office. In this capacity, he provides litigation support and e-discovery assistance on complex criminal cases to defense teams around the country. Before entering private practice, Mr. Ellis spent 13 years as a trial attorney and supervisory attorney with Federal Defenders of San Diego, Inc. He also serves as a digital forensic consultant and expert.]

Introduction

This is an updated version of a post originally published in December 2020, which provides a primer on how Google collects location data, the three-step warrant process used by law enforcement to obtain these records, and an example of how the data is collected and used by the prosecution. The updated version includes references to United States v. Chatrie, a recently decided district court opinion regarding the constitutionality of geofence warrants.[i] From the opinion and the pleadings in Chatrie, we have a better understanding of the Google collection and geolocation search warrant process.

What Can Google Do?

Google began collecting location data in order to provide location-based advertisements to its’ users. Google tracks location data from the users of its products, including from consumers who use Android telephones and those who use Google’s vast array of available apps on other devices such as Apple iPhones. For Android devices, Google is constantly tracking devices whenever the permission settings on the device are set to allow for the use of Google Location Accuracy. For iOS users, location information is only collected when a user is using a Google product, such as Google Maps.[ii] Google stores this information in a repository called “Sensorvault”, which “assigns each device a unique device ID…and receives and stores all location history data in the Sensorvault to be used in ads marketing.” 3:19-cr-00130-MHL at 7. The use of Sensorvault has been very profitable for Google. Since Google started collecting data and using Sensorvault in 2009, Google’s advertisement revenue has almost increased tenfold.

See https://www.statista.com/statistics/266249/advertising-revenue-of-google.

Google is able to determine the approximate location of a mobile device based on GPS chips in the device, as well as the device’s proximity to Wi-Fi hotspots, Bluetooth beacons, and cell sites.[iii] For purposes of Wi-Fi, Google uses the characteristics of wireless access points within range of the device (including received signal strength) to determine the device’s proximity to the access point, and thus approximate location. How Google tracks this data is dependent of the type of device (Android v. Apple) and an individual user’s privacy settings.[iv] Google cannot determine the exact location of a device, and as such, location records contain an “uncertainty value” which is expressed in meters.

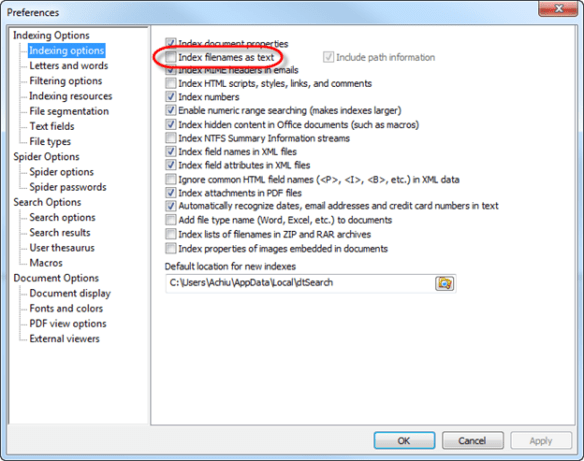

Maps Display Radius:

Because Google does not know a device’s precise location, it represents the possible location in a sphere, or what Google refers to as the Maps Display Radius.

In this picture, Google’s “goal is that there will be an estimated 68% chance that the user is actually within” the spherical representation.[v]

To see how Google determines the approximate location of a mobile device, viewing the Location History of a Google account is instructive. In the following example, according to Google, the blue line indicates the path of travel, the orange dots represent wireless access points, and the grey sphere next to the blue arrow is the estimated range of the location source.

Generally, the location information source has the largest impact on the Maps Display Radius. Most often, GPS provides the smallest sphere whereas Cell Sites are generally the largest. By way of example, the map display radius for GPS is often a few meters whereas Wi-Fi is routinely over 1000 meters.

Use of Google’s Tools by Law Enforcement – Three-Step Warrant Process

Although the original intent of Google’s Sensorvault technology was to sell advertising more effectively, over the past few years this data has been sought by law enforcement to determine who was present in a specific geographical area at a particular time, for example, when a crime was committed. These warrants are often called “Geofence warrants” because officers seek information about devices contained within a geographic area. In 2021, Google released information about the number of geofence warrants sought by law enforcement. According to the data, “Google received 982 geofence warrants in 2018, 8,396 in 2019 and 11,554 in 2020.”[vi]

In current practice, Google requires law enforcement to obtain a single search warrant. The three stage warrant process is based on an agreement between Google and the Department of Justice’s Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section (CCIPS). Once Google receives a geofence warrant, it takes on the extrajudicial role of determining when law enforcement officers have complied with probable cause such that additional information will be provided.

Stage One:

In response to the warrant, “Google must ‘search … all [Location History] data to identify users’ whose devices were present within the geofence during the defined timeframe” and to provide a de-identified list of such users. Chatrie at 19. The list includes: (1) anonymized user identifiers; (2) date and time the device was in the geofence; (3) approximate latitude and longitude of the device; (4) the maps display radius; and (5) the source of the location data.[vii]

Stage Two:

After reviewing the initial list, law enforcement can return to Google and request additional information about any device that is within in the first geofence. This includes “compel[ling] Google to provide additional…location coordinates beyond the time and geographic scope of the original request.” Chatrie at 21.[viii] Troubling,

Google imposes “no geographical limits” for Stage Two review. Id.

Stage Three:

The third step involves compelling Google “to provide account-identifying information for the device numbers in the production that the government determines are relevant to the investigation. In response, Google provides account subscriber information such as the email address associated with the account and the name entered by the user on the account.”[ix]

It is important to note that in practice it appears that law enforcement routinely skips Stage Two and moves directly from Stage One to Stage Three analysis.

Past Examples

The shape of Google Geofence warrants has changed over time. For instance, In the Matter of the Search of information that is stored at premises controlled by Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, California 94043, law enforcement officers investigating a bank robbery sought information about “all Google accounts” located within a 30 meters radius around 43.110877, -88.337330 on October 13, 2018, from 8:50 a.m. to 9:20 a.m. CST.

Compare that to In the Matter of the Search of Information Regarding Accounts Associated with Certain Location and Date Information, Maintained on Computer Servers Controlled by Google, Inc.. In that instance, law enforcement was investigating a series of bombings and they sought location information for “all Google accounts” for a 12-hour period between March 1 and 2, 2018 in a “[g]eographical box” around 1112 Haverford Drive, Austin, Texas, 78753 containing the following coordinates: (1) 30.405511, -97.650988; (2) 30.407107, -97.649445; (3) 30.405590, -97.646322; and (4) 30.404329, -97.647983.

More recently, Google has requested that law enforcement submit Geofence warrants that are convex polygons in shape.

Starting from the Beginning – How the Process Works

To put this into perspective, the following example is illustrative. For these purposes, a crime occurred in the parking lot of a strip mall.

Because the crime occurred in the middle of a parking lot, we will create a geofence that includes storefronts because it will increase the chances that the suspect’s mobile device will be within range of a Wi-Fi hotspot or Bluetooth beacon. Conversely, the geofence will include the mobile devices of numerous people who are not connected to the offense.

The above geofence appears to only impact people who are present in the parking lot or surrounding business. However, the geofence would likely capture many more people, including people living or visiting in the nearby apartments and anyone who was driving on the surrounding streets during the time in question.

Stage One—The following is an example of a Stage One warrant return:

| Device ID | Date | Time | Latitude | Longitude | Source | Maps Display Radius (m) |

| 123456789 | 12/20/20 | 15:08:45(-8:00) | 32.752667 | -117.2168 | GPS | 5 |

| 987654321 | 12/20/20 | 15:08:55(-8:00) | 32.751569 | -117.216647 | Wi-Fi | 25 |

| 147852369 | 12/20/20 | 15:08:58(-8:00) | 32.752022 | -117.216369 | Cell | 1000 |

| 123456789 | 12/20/20 | 15:09:47(-8:00) | 32.752025 | -117.216369 | Cell | 800 |

| 987654321 | 12/20/20 | 15:09:55(-8:00) | 32.752023 | -117.216379 | Wi-Fi | 15 |

| 123456789 | 12/20/20 | 15:10:03(-8:00) | 32.752067 | -117.216368 | Wi-Fi | 25 |

| 987654321 | 12/20/20 | 15:10:45(-8:00) | 32.752020 | -117.216359 | Cell | 450 |

| 987654321 | 12/20/20 | 15:10:55(-8:00) | 32.752032 | 117.216349 | Wi-Fi | 40 |

| 123456789 | 12/20/20 | 15:10:58(-8:00) | 32.752012 | 117.216379 | Cell | 300 |

Here, Device ID 123456789 is Suspect One, Device ID 987654321 is Suspect Two, and Device ID 147852369 is Suspect Three. For this example, only one location for each device is shown.

At first blush, it would appear as if the Geofence has located three possible suspects. But this image does not tell the full story. The blue bubbles for Suspect One and Suspect Two show a Maps Display Radius of 5 and 25 meters respectfully.

Suspect Three’s location was derived from a Cell Site, with a Maps Display Radius of 1000 meters.

Thus, although Google believes that Suspect Three’s device was near the scene of the crime, it is possible it was located anywhere within the larger sphere, and it is possible that the device was not located within either sphere.

Stage Two—For this stage, we can expand our original results, as long as we only include one of the accounts returned in Stage One. Here, we will expand our results and determine if Suspect One’s device also present in the area Northeast of the original search location.

Stage Three—is the step whereby subscriber information about the accounts Google deems responsive. Meaning, law enforcement requests Google to provide the account number and information for Device IDs provided in either Stage One or Two. The following is an example of such a return:

Conclusion As technology and privacy concerns of consumers continue to change, so will the ability for law enforcement to obtain location data of users. The use of Google geofence warrants implicates a number of Fourth Amendment issues; future posts will explore the legal implications surrounding the overbreadth of these warrants.[x] But beyond the legal challenges, those encountering Google location warrants should remain mindful of the limitations of the data as well as the absence of concrete answers from Google regarding their methodology for determining location data

[i] See United States v. Chatrie, 3:19-cr-00130-MHL, Docket Entry 220.

[ii] The exception is for a user who has turned location services to always on, has a Google product open on a device, and has allowed for background app refresh. That means that is likely that Google knows far more about the location history of android users than iPhone users. That’s important because approximately 52 percent of devices on mobile networks are iOS devices. https://www.statista.com/statistics/266572/market-share-held-by-smartphone-platforms-in-the-united-states/.

[iii] https://policies.google.com/technologies/location-data (“On most Android devices, Google, as the network location provider, provides a location service called Google Location Services (GLS), known in Android 9 and above as Google Location Accuracy. This service aims to provide a more accurate device location and generally improve location accuracy. Most mobile phones are equipped with GPS, which uses signals from satellites to determine a device’s location – however, with Google Location Services, additional information from nearby Wi-Fi, mobile networks, and device sensors can be collected to determine your device’s location. It does this by periodically collecting location data from your device and using it in an anonymous way to improve location accuracy.”)

[iv] https://support.google.com/nexus/answer/3467281?hl=en

[v] See United States v. Chartrie, 19cr00130-MHL (EDVA 2020), ECF 1009 [Declaration of Marlo McGriff] (“A value of 100 meters, for example, reflects Google’s estimation that the user is likely located within a 100-meter radius of the saved coordinates based on a goal to generate a location radius that accurately captures roughly 68% of users. In other words, if a user opens Google Maps and looks at the blue dot indicating Google’s estimate of his or her location, Google’s goal is that there will be an estimated 68% chance that the user is actually within the shaded circle surrounding that blue dot.”)

[vi] https://techcrunch.com/2021/08/19/google-geofence-warrants/

[vii] Id. at 4 (“After that search is completed, LIS assembles the stored LH records responsive to the request without any account-identifying information. This deidentified ‘production version’ of the data includes a device number, the latitude/longitude coordinates and timestamp of the stored LH information, the map’s display radius, and the source of the stored LH information (that is, whether the location was generated via Wi-Fi, GPS, or a cell tower)”).

[viii] Id. at 17

[ix] Id.

[x] In the Matter of the Search of: Information Stored at Premises Controlled by Google, 20mc00392-GAF (NDIL 2020) provides a great overview of the Fourth Amendment issues relating to Google Geofence warrants. See also https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/07/eff-files-amicus-brief-arguing-geofence-warrants-violate-fourth-amendment

[Editor’s Note:

[Editor’s Note: