[Editor’s Note: Tom O’Connor is an attorney, educator, and well respected e-discovery and legal technology thought leader. A frequent lecturer on the subject of legal technology, Tom has been on the faculty of numerous national CLE providers and has taught college level courses on legal technology. He has also written three books on legal technology and worked as a consultant or expert on computer forensics and electronic discovery in some of the most challenging, front page cases in the U.S. Tom is the Director of the Gulf Coast Legal Technology Center in New Orleans, LA ]

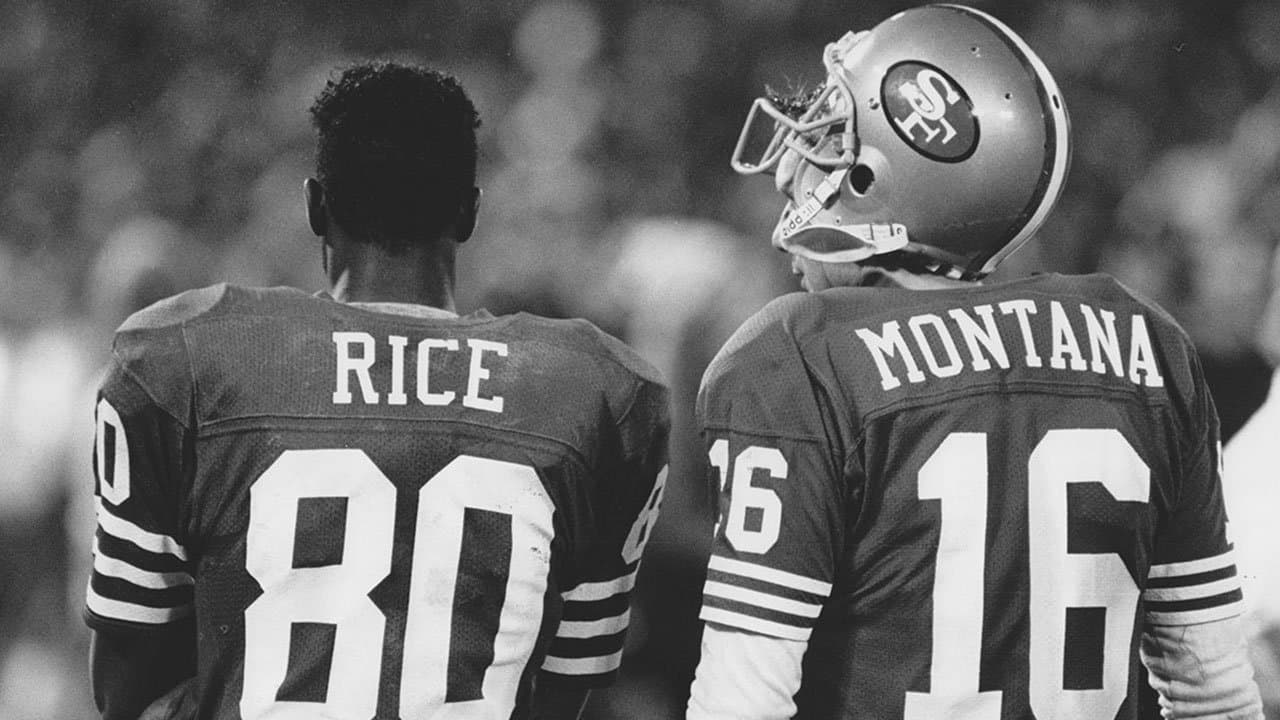

If you were practicing in federal court before email, ECF filing, and in the days when Joe Montana threw to Jerry Rice then you probably remember discovery productions were typically hardcopy documents you picked up at the US Attorney’s Office. The volume was so small it easily fit into your briefcase. Those were the days when everyone complained about not getting enough discovery. The challenge was moving to compel for more discovery when you didn’t know what you didn’t have.

Fast forward to the present. Tom Brady is throwing to Rob Gronkowski (again but in a different city) and discovery is typically so voluminous it cannot be provided in hardcopy form. Productions can be hundreds of gigabytes and sometimes dozens of terabytes full of investigative reports, search warrant pleadings, surveillance audio and video, cell phone data, cell tower material, years of bank records, GPS data, social media materials, and forensic images of servers, desktop computers, and mobile devices. Common are duplicate folders of discovery produced “in the abundance of caution” to protect the Government against Brady violations. Despite the volume, the same issue exists: How do you know what you don’t have?

US v Morgan (Western District of New York, 1:18-CR-00108 EAW, decided Oct 8, 2020) is an example of diligent defense counsel challenging the government on how it produced terabytes of data.

Defendants Robert Morgan, Frank Giacobbe, Todd Morgan, and Michael Tremiti were accused by way of a 114-count Superseding Indictment of running an illegal financial scheme spanning over a decade. The government alleged they defrauded financial institutions and government sponsored enterprises Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae in connection with the financing of multi-family residential apartment properties that they owned or managed. There were also allegations of related insurance fraud schemes against several of the defendants.

The government made several productions which the defense contended were deficient (including the lack of metadata on numerous documents) and, in several cases, omitted key pieces of evidence. The defense enlisted the help of e-Discovery experts, who stated the government failed to properly process and load evidence into their database for production to defense counsel.

The issue was brought before the court in defense motions to compel and dismiss. First to the magistrate judge then to the district court judge, which resulted in a critical analysis of the way the government handled the discovery.

CASE TIMELINE

The original status conference in the case was held on May 29, 2019. For the next year, a series of motions and hearings proceeded with regards to delays and failures on the part of the government to meet discovery deadlines imposed by the court.

An evidentiary hearing was finally held before district court Judge Elizabeth A. Wolford on July 14, 2020, continuing through the remainder of that week until July 17, 2020, and then resumed and concluded on July 22, 2020. There were multiple expert witnesses, and the review of that testimony is over 7 pages in the Opinion.

On September 10, 2020, oral argument on the motions to compel and dismiss was heard before Judge Wolford. The Court entered its Decision and Order on October 8, 2020.

There was no dispute that the discovery in this matter was not handled properly. In the second paragraph of the above cited Decision and Order, Judge Elizabeth A. Wolford states,

“The Court recognizes at the outset that the government has mishandled discovery in this case—that fact is self-evident and cannot be reasonably disputed. It is not clear whether the government’s missteps are due to insufficient resources dedicated to the case, a lack of experience or expertise, an apathetic approach to the prosecution of this case, or perhaps a combination of all of the above.”

Specifically, the government somehow failed to process and/or produce ESI from several devices seized pursuant to a search warrant executed in May 2018 and in one case, a cell phone, seems to have actually been lost. The court ultimately dismissed the case without prejudice. This gave the parties time to resolve the discovery issues. On March 4, 2021, a grand jury returned a new 104 count indictment.

More important for our purposes are the discussions regarding the ESI and production issues. They are outlined below.

PROJECT MANAGEMENT

The Court wasted no time in saying “It is evident that the government has demonstrated a disturbing inability to manage the massive discovery in this case, and despite repeated admonitions from both this Court and the Magistrate Judge, the government’s lackadaisical approach has manifested itself in repeated missed deadlines.”

And later, “To be clear, the Court does not believe the record supports a finding that any party acted in bad faith. Rather, the discovery in this case was significant, and the government failed to effectively manage that discovery. In the end, because of its own negligence, the government did not meet the discovery deadline set by the Magistrate Judge.”

COMPLEXITY OF LARGE AMOUNTS OF ESI

Judge Wolford made several references to the “massive discovery.” In an attempt to manage that data, the Magistrate Judge had initially directed the parties to draw up a document entitled “Data Delivery Standards” (hereinafter referred to as “the DPP”) which would control how documents were exchanged. It failed to do so for several reasons.

First was the large amount of data. Testimony by a defense expert witness at the evidentiary hearing of July 14, 2020, stated that “… the government’s Initial Production consisted of 1,450,837 documents, reflecting 882,841 emails and 567,996 other documents. Of those documents, 860,522 were missing DATE metadata, with over 430,000 documents reflecting no change in the DATE metadata field formatting after the DPP was agreed-upon. Once overlays were provided by the government, the DATE metadata field was corrected for almost one-third of the documents (primarily emails), but 590,448 documents still were missing DATE metadata, including 294,818 emails. Of those 294,818 emails, 169,287 had a misformatted DATE value and 125,531 had no DATE value. The Initial Production also contained missing values for the metadata fields of FILE EXTENSION, MD5 HASH, PATH, CUSTODIAN, MIME TYPE, and FILE SIZE— and the government overlays did not change the status of the information in any of those fields.”

Additionally, the USAO-WDNY’s processing tool was Nuix while another entity—the Litigation Technology Support Center in Columbia, South Carolina – processed some of the hard drives using a different processing tool called Venio. Additionally, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (“FHFA”) processed the Laptop Production using a “much more robust” version of Nuix than the system possessed by the USAO-WDNY.

These differing versions led to different productions which had different values for the metadata fields. Standardization on one tool could have prevented much of this. But the Court also noted that “… the quality review conducted by the government was insufficient to catch these errors.”

Inconsistent directions were an ongoing issue. For example, the Court found that “… the government prosecutors expressly instructed Mr. Bowman not to produce CUSTODIAN information for the Laptop Production, even though the government had provided similar information previously.”

Other government errors included:

- It applied different processing software inconsistently to the PST or OST files, thereby missing some metadata and producing varying results.

- It misformatted the DATE metadata caused by failing to catch the errors while conducting a quality review.

- It failed to produce native files in “the format in which they are ordinarily used and maintained during the normal course of business[.]” It produced near native or derivative native files from the OST or PST files without corresponding metadata.

- In many instances, load files necessary to install the document productions in the defense review software platform were missing.

- There were ongoing errors with respect to CUSTODIAN metadata, which were the result of human error on the part of the government.

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN TO YOU?

With regards to what specific steps can be used to take control of cases with large amounts of ESI, the Court mentioned several.

- Use an exchange protocol. In civil cases, this document would arise from FRCP Rule 26(f), which mandates a “Meet & Confer” conference of the parties so that they might plan for discovery through the presentation of a specific plan to the Court.

In Morgan, this was the document entitled the DPP. In criminal cases going forward, the new Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 16.1 will address some of these concerns. Drawn up specifically as a response to deal with the manner and timing of the production of voluminous Electronically Stored Information (ESI) in complex cases, Subsection (a) requires the prosecution and defense counsel to confer “[n]o later than 14 days after the arraignment…to try to agree on a timetable and procedures for pretrial disclosure under Rule 16.1.” Subsection (b) authorizes the parties, separately or together, to “ask the court to determine or modify the time, place, manner or other aspects of disclosure to facilitate preparation for trial.”

- Standardize the use of technology. As Judge Wolford said, “In sum, the Court believes that it would have been much more prudent if the government, after reaching agreement with the defense about the DPP, had utilized a competent vendor to process the ESI (and all the previously produced ESI) in the same manner with the same settings and utilizing the same tools.”

- Get a data manager. A common saying in IT circles is that “someone needs to own the data.” In this case, where the Government used multiple parties who employed different tools to work with the data, nobody owned the data. This lack of a central manager “… led to electronic productions being produced in an inconsistent manner and, in some instances, in violation of the DPP.”

- Get an expert. After hearing multiple experts testify for several days on what had transpired with the ESI, the Court noted, “… electronic discovery is a complicated and very technical subject. As a result, facts can be easily spun in a light most favorable to one party’s position or the other. That occurred here on behalf of all parties.”

Nonetheless, the experts were able to bring clarification to the issues of “missing” metadata and divergent processing results that had beleaguered the parties and the Court. This field, especially with large amounts of ESI, is a classic example of the old maxim, “do not try this at home.” Get an expert.

- Use a review tool. ESI in these large amounts are simply not able to be reviewed manually. Both parties here recognized that fact and, as the Court noted several times, most of the errors in the case were not due to software but what we nerds call the “loose nut on the keyboard” syndrome.

Get review software. Get trained on it. Use it. One admonition I always make which could have avoided many delays in this matter is do not try to load everything at once into your review platform. Start with a small amount of sample data to be sure you are getting what you need. Which leads to our last takeaway.

- Talk with the government. Judge Wolford specifically noted that the “… the Court also concludes that Defendants and the government were not always communicating effectively regarding electronic discovery.” For example, none of the parties could recall “… any discussions during those negotiations about the processing tools that would be utilized or the type of native file that would be analyzed for purposes of creating a load file.”

CONCLUSION

The Morgan case illustrates there are ways to learn about what you don’t have so you can bring it to the government’s attention and if need be, to the Court. It is also example of a Court being knowledgeable about ESI productions. The Court noted often and in different ways that “… electronic discovery is challenging even under the best of circumstances. In other words, the facts and circumstances cannot be appropriately evaluated without considering the volume of discovery and the enormous efforts needed to manage an electronic production of this nature.”

Find an expert who understands your needs and has effective communication skills to convey to you, the government, and Court complex technical issues. For many years, Magistrate Judge Andrew Peck (SDNY, Retired) advocated “Bring-Your-Geek-To-Court Day,” in which parties bring an outside consultant or an in-house IT person to address disputes. If you were to remember only one thing form this case, it should be: Go get a geek.

Tom O’Connor

Director

Gulf Coast Legal Tech Center

toconnor@gulfltc.org

www.gulfltc.org

Blog: https://technogumbo.wordpress.com/

Twitter: @gulfltc